THE PHONOLOGY (SOUND SYSTEM) OF AVESTAN. GENERAL REMARKS.

One of the things that strikes one about Avestan as opposed to Old Indic (Sanskrit) is the seemingly chaotic orthography. The cause of this state was long thought to be that the Avestan text had been corrupted by the manuscript writers, and scholars therefore decided that the text had to be "corrected" and

![]()

'normalized" in order to recapture the "original" Avestan text. They never proved their point by examining in detail the orthography and the individual characteristics of the manuscripts, however.

The first Western scholar to undertake a complete analysis of the phonology of Avestan was G. Morgenstierne, who in an article written during World War Il and published in 1942 showed that the Avestan alphabet reflected an internally consistent phonological system, in many respects similar to those of living Iranian dialects and languages. Most of the seemingly orthographic aberrations, which at the time were commonly explained as scribal errors, could be explained in terms of the phonological system of the language(s) of the Avesta.

It must be kept in mind, however, that the Avestan texts as we have them do not necessarily in every detail reflect a genuine linguistic system. For centuries they were adjusted by editors (diascevasts) and then by scribes who spoke dialects or languages with phonological systems differing fundamentally from that of the original Avestan language. Thus, on one hand, the Old Avestan texts contain many elements that are clearly borrowed from or influenced by Young Avestan, and, on the other hand, the Young Avestan texts contain both elements that are imitations of Old Avestan ("pseudo-OAv.") and elements belonging to later stages of Iranian that were probably introduced by the scribes.

It is, finally, almost impossible to determine which of the sound changes we observe in our extant manuscripts already belonged to the original language and which ones were introduced at various stages of the 1000-1500 years' oral and written transmission of the texts. One way of determining early changes is to compare the Avestan phonological system with that of Old Indic.

As much of the transmission of the surviving Avesta probably took place in southwestern Iran, phonological changes shared with other East-Iranian languages as opposed to West-Iranian languages may be assumed to belong to the early period.

One such typically East-Iranian sound

change is the shortening of ï and its disappearance in juua-"alive, ![]() which

agrees with Sogdian žw-, Khotanese juva-, and Pashto žw-, against Olnd. jïva-;

and in cuua?t- "how great," Olnd. kïvant-.

which

agrees with Sogdian žw-, Khotanese juva-, and Pashto žw-, against Olnd. jïva-;

and in cuua?t- "how great," Olnd. kïvant-.

Palatalization and labialization of vowels, however, which is typical of the transmitted Avestan text, are also found in western Iranian languages and do not necessarily belong to the eastern stage of the transmission.

Important:

Some students may find it useful to compare Sanskrit (Old Indic) when learning the Avestan grammar, but both they and the teachers should avoid phonetically "translating" the Avestan into Sanskrit to explain the Avestan forms. Such an approach not only hints at an "inferior" status of Avestan compared to Sanskrit but also—more importantly—may take the focus away from the linguistic structure of Avestan in its own right—its phonetic and grammatical systems and the indigenous semantic developments. In my own experience, students who routinely see the Sanskrit forms in the Avestan ones may experience great difficulties in identifying typically Avestan, especially "contracted," forms.

The students are not expected to master completely the following description of the phonological system of Avestan right away but use it for reference.

2()()3

PHONEMES

We call "phonemes" the smallest units of speech that distinguish meanings. Phonemes are usually determined by exhibiting "minimal pairs," e.g., English bad sad, a pair that establishes /b/ and Is/ as separate phonemes in English.

Phonemes are denoted by writing them between / ,/. The phoneme is not a "sound" (the sound that somebody produces and which we hear when somebody speaks) but a linguistic entity devised, as it were, to provide the theoretical link between acoustic sound (the "physical" aspect of speech) and meaning (the "psychological" aspect of speech).

When we want to emphasize that we are talking about the actual sound, or the "phonetic realization" of a phoneme, we use square brackets [ ] , e.g., [p], [b], [z]. These actual sounds are also called "phones" or "allophones."

Phonemes are described by listing their "distinctive features." These distinctive features are descriptions of how the sound is produced in the mouth and which parts of the mouth are involved in the sound production. Following are some examples:

/b/: stop, labial, voiced — /p/: stop, labial, unvoiced, — /m/: nasal, labial.

/x/: fricative, velar, unvoiced /y/: fricative, velar, voiced.

/s/: sibilant, alveo-dental, unvoiced /z/: sibilant alveo-dental, voiced /š/: sibilant, alveo-palatal, unvoiced /ž/: sibilant, alveo-palatal, voiced.

Note that English t is sometimes aspirated [t h], sometimes not aspirated [t]. The feature "aspiration" is not, however, distinctive in English or Avestan, so there is no phonemic opposition It/ /th/, "p/ ph/, etc. In such cases we say that [p] and [ph] are "allophones" of /p/. Aspiration is a distinctive feature in some languages—Sanskrit, for instance, where we have minimal pairs such as kara [kara] "hand" khara [khara] "donkey."

![]() In

the case of In/ we note that "voiced" is not a distinctive feature of

nasals in English or Avestan, as no two words can be distinguished by the

presence or absence of voicing in a nasal /n/. On the other hand, Avestan has a

voiceless or, probably, pre-aspirated [hm], which may be a separate phoneme:

/m/ / hm/, but more probably it is simply an allophone of 1m/ after

h or alternative (short-hand) way of writing hm.

In

the case of In/ we note that "voiced" is not a distinctive feature of

nasals in English or Avestan, as no two words can be distinguished by the

presence or absence of voicing in a nasal /n/. On the other hand, Avestan has a

voiceless or, probably, pre-aspirated [hm], which may be a separate phoneme:

/m/ / hm/, but more probably it is simply an allophone of 1m/ after

h or alternative (short-hand) way of writing hm.

PHONEMIC NEUTRALIZATION

Phonemes may not be distinguished in all positions. Thus, in English we cannot find any minimal pairs distinguished by the phoneme sequences /st/ and /sd/. In such cases we say that the phonemic opposition between /t/ and /d/ has been neutralized after /s/.

VOWEL PHONEMES

Vowel phonemes are defined by features relating to the position of the tongue in the mouth and the shape of the lips. There are three basic parameters:

1 . The height of the highest point of the tongue: high - mid - low.

2. The place of the highest point of the tongue: front - central - back.

3. Rounding or non-rounding of the lips.

In Avestan there are the additional features of short - long and of nasalized - oral (= non-nasalized), only some of which have distinctive function.

Diphthongs may be regarded as combinations of phonemes or single, composite, phonemes.

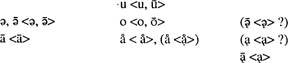

We may tentatively posit the following vowel (simple and diphthongs) phonemes for Young Avestan (spelling in < >):

2()()3

Front Central Back, rounded Nasal

Mid

Mid ![]()

Low ![]()

|

Diphthongs: Short |

|

|

|

ai <aë> |

oi/oi <öi> |

ãi <äi> |

au

<ao, aö> ou

<ou> au![]()

The difference between õ and ci must have been between closed and open [o: å:] (approximately as in English home hawk, Germ. rote Rotte).

Cf. the following minimal or almost minimal pairs:

äpõ apõ "waters" nom. plur. gen. sing., acc.

plur. apõ apa "water" gen. sing., acc. plur. instr. sing. amanz —

imam "the strength" ![]() apa

upa "with water" "up to, at" aspõ aspa asp5

"horse" nom. sing. instr. sing. acc. plur.

apa

upa "with water" "up to, at" aspõ aspa asp5

"horse" nom. sing. instr. sing. acc. plur.

![]() surõ

surå "rich in life-giving strength" masc. nom. sing. fem. nom.-acc.

plur. aêta aête "this" instr. sing. nom. plur. äiš aêša "with

these" "this (one)" gäuš gaoš g5uš "cow" noni. gen.

gen. parana- parana- "feather"

surõ

surå "rich in life-giving strength" masc. nom. sing. fem. nom.-acc.

plur. aêta aête "this" instr. sing. nom. plur. äiš aêša "with

these" "this (one)" gäuš gaoš g5uš "cow" noni. gen.

gen. parana- parana- "feather" ![]() mašiia-

amaša- "(mortal) man" "immortal" kaša O kaša

"armpit" "-cutters" tê — tq "they" and haonza

haomq "haoma" plur. nom. acc.

mašiia-

amaša- "(mortal) man" "immortal" kaša O kaša

"armpit" "-cutters" tê — tq "they" and haonza

haomq "haoma" plur. nom. acc.

The phonemic status of vowel length in the case of i and i, u and ü is uncertain. Standard editions and grammars give the impression that the distribution of short and long i and u (in Young Avestan) is conditioned by phonetic context and that they are therefore in complementary distribution, but the distribution of i and i, u and in the actual manuscripts has not been investigated in any detail, and from the studies that have been made (e.g., Hintze in JamaspAsa, 1991), it appears that the choice between i or i, u or 1.7 Inay be a matter of scribal preference. Thus, the distribution by phonetic context may be a mirage of Western editions and not supported by the manuscripts.

Note that in relatively modern Iranian manuscripts long 17 is replaced by i. Investigation of this phenomenon may help establish the correct distribution of u or 17.

In this manual, long and are used in final position in monosyllables only (zï, nü) and separated preverbs (nï. 0 , vï. 0 ), as well as to indicate stem forms (tanü-, etc.), but in all other cases short i and u are used consistently (with a few exceptions in the reading exercises), in order to stress the fact that the choice of (Young) Avestan short or long i and u is not conditioned by their origins, such as Proto-Iranian short and long i and u or by their being contraction products (*-im, *-7m, and *-iiam all > -im or -ïm and *-um, *-17m, and *-uuam all > -um or -17m). Obviously, long and could also have been ušed.

The same caveat may to sonle extent apply

to short and long e and ê, o and (5. Thus, in our standard editions, other than

in monosyllabic words (see below), is restricted to the diphthong aë, while õ,

other than as word final and composition vowel is only found before the

morpheme border. Pairs such as vohu and

dänzõhu do not, therefore necessarily prove

a phonemic opposition o (5. The distribution of o — ![]() also

varies by manuscripts, however. Thus, many manuscripts have consistently võhu

instead of vohu, and for the diphthong ao many manuscripts commonly have aõ.

also

varies by manuscripts, however. Thus, many manuscripts have consistently võhu

instead of vohu, and for the diphthong ao many manuscripts commonly have aõ.

2003

å was an allophone of before 0, It, and s.

[The short is found in a single manuscript (Pd) for short a before O.]

Q was an allophone of ä before n or m, e.g., nvna or näma. In the accusative plural it is in complementary distribution with 5, and so apparently stands for *Q or The two letters Q and Q (*e) are used indiscriminately in the extant manuscripts. In Geldner's edition is the "default" letter.

The primary diphthong aë is never found in final syllable, open or closed. In final closed syllable, aë is the result of contraction (e.g., -aëm < *-aiiam).

The diphthong õi appears to be an allophone of aë used primarily in closed syllables. Thus, in Young Avestan õi is preferred before consonant clusters, though not before s or š plus one consonant. [1]

The only apparently minimal pair for aë — õi is aëm "he" — õim "one" (< aëuua-). Instead of õim we also find the spelling aoim, so õim may be just a manuscript variant of aoim. In the table above it is suggested that õi is structurally for /oi/. It occurs occasionally in monosyllables instead of ê, e.g., yõi but të.

Note: aë is never used in final syllable, open or closed.

The diphthong ãu is used in a small number of words as a variant of ao, probably in imitation of Old Avestan.

The diphthong ou is only found as the result of labialization (see the next lesson), e.g., pouru < *paru. In the manuscripts it is also written õu (põuru).

EXERCISES 2

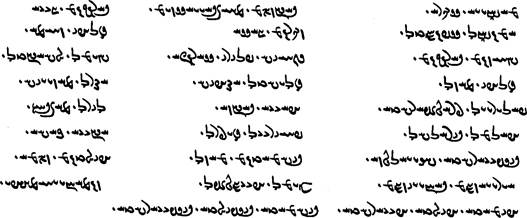

I. Practice reading and pronouncing the following words and phrases and translate them:

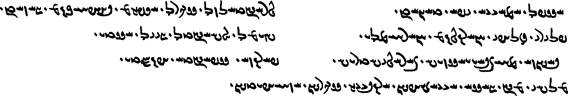

2. Read and try to translate the following sentences:

2003